The Big Problem With High Health Care Deductibles

Janill Gilbert stashed this in Medical

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/07/upshot/the-big-problem-with-high-health-care-deductibles.html

When Bernie Sanders released his long-awaited health care plan last month, it was light on the details. But it did include one major, crowd-pleasing promise: Under his Medicare-for-all proposal, no American would ever have to pay a deductible or co-payment to receive health care again.

Deductibles and other forms of cost-sharing have been creeping up in the United States since the late 1990s. A typical employer health plan now asks an individual to pay more than $1,000 out of pocket before coverage kicks in for most services. The most popular plans on the Affordable Care Act exchanges require customers to pay several times as much. Even Medicare charges deductibles.

People tend to hate these features, but they were not devised to be cruel. Rather, they were fashioned with economic theory in mind.

Deductibles and co-payments are intended to make patients behave more like consumers in other parts of the economy. People who have to pay the full cost of magnetic resonance imaging on their knee, for example, might be more likely to shop around and pick the $500 one instead of the $3,000 one. Perhaps, they’ll decide to give their minor knee pain two weeks to see if it gets better on its own, and skip the M.R.I. The hospital offering the $3,000 M.R.I. might lose enough business that it will lower its price.

Those choices, over time, could reduce the amount of health care that is used and the price of services: If patients do not care about price, then they will not have any incentive to look for a bargain, and health care providers will not have an incentive to offer one.

A famous randomized experiment in the 1970s and ’80s helped demonstrate that at least part of this theory worked. Researchers from the RAND Corporation gave insurance with high cost-sharing to some people and lower cost-sharing to others. Over time, the researchers found that the people who had to pay more of their bills in cash used less health care and were no less healthy than people whose insurance covered everything.

“If you make something free, people will spend a lot on it,” said Michael Chernew, a professor of health policy at Harvard, who studies ways to control health care costs. Mr. Chernew and co-authors have argued that the emergence of plans that require more out-of-pocket spending is most likely responsible for part of a recent slowdown in the growth of health spending.

More recent research supports this idea. Employers who asked workers to pay a higher share of their bills have also seen overall spending decline. A particularly good case can be made that cost-sharing has helped steer patients away from brand-name drugs and toward identical generics, when they are available.

But the type of cost-sharing can make a big difference, and new research suggests that high deductibles in particular may not work as intended. A team of researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, and Harvard recently published a working paper on what happened when a large (unnamed) employer switched from a more generous health plan to one with a high deductible. The typical worker in the company was young and Internet savvy, and earned more than $125,000 a year. The company gave employees a web tool to compare health care prices, and a health savings account for the full amount of the deductible, so they wouldn’t actually have to pay any bills out of their salaries. Amitabh Chandra, an economist at Harvard, and one of the researchers, said he was convinced the study would prove the value of deductibles, at least for well-off and well-educated workers.

He was wrong. Over all, the workers did spend less on health care. Spending fell by about 12 percent, a remarkable decline. But the way workers achieved those savings gave the researchers pause. There was no evidence that workers were comparing prices or making wise choices on where to cut, even after two years in the new plan. They visited the same doctors and hospitals they always had. They reduced low-value medical services and medically important ones at about the same rate, raising questions about their long-term health.

Mr. Chandra said he was no longer convinced that deductibles turned patients into good consumers. “The best case was the theoretical case,” he said. “I was all for high-deductible plans before I wrote my paper.”

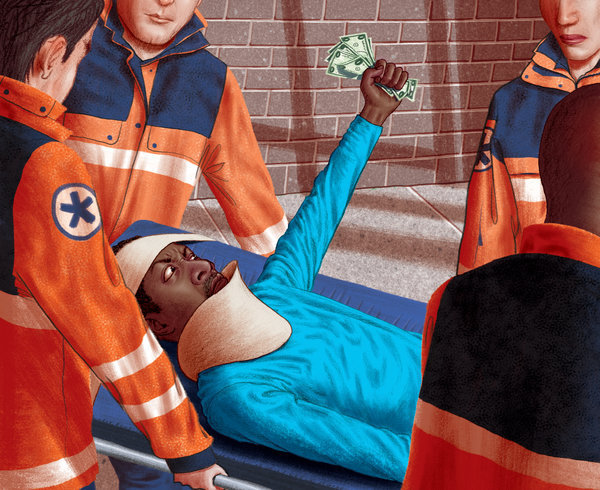

The other problem with high deductibles is the obvious one: Many Americans simply do not have the savings to afford them. In partnership with the Kaiser Family Foundation, we recently conducted a survey of Americans struggling with their medical bills. A substantial fraction of them could not pay their deductibles and were left with tough choices about how to cut thousands of dollars from their household budgets to pay for health care.

For those people, deductibles often seem like an unfair trick, or a feature that makes insurance worthless. More than 3,000 readers wrote us about that medical debt article, many deploring high deductible health plans that had put them in financial distress.

Dr. Peter B. Bach, an oncologist and the director of the Center for Health Policy and Outcomes at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, said he had seen patients discontinue lifesaving treatments when the year ran out, because they could not afford another big deductible. He argued that the problem with deductibles was that few people really can control whether or when they will be struck by an illness that requires expensive treatment. “There’s essentially nothing they can do to prevent the likelihood they’ll have high-cost health events,” he said.

But, even if deductibles have their downsides, it seems clear they have helped make insurance more affordable. Without them, far fewer Americans would be able to pay for health insurance at all.

Some health economists say the solution to the problem may be smarter but more complicated forms of health insurance that provide patients with important care free, but charge them for treatments with fewer proven benefits. Mr. Chernew, for one, argues that ordinary deductibles are too “blunt” an instrument, but smarter insurance plans could harness economic incentives to reduce wasteful health spending without discouraging needed care. If such plans held down costs as well as deductibles, they could keep insurance affordable without as many risks. The theory behind such plans is compelling, but given how bad people are at shopping for health care, more empirical evidence is needed to know how well it works in practice.

Stashed in: @troutgirl, Awesome, Healthcare, Health, Personal Finance, Healthcare!

I have to laugh whenever economists whip out the old tired canard of how consumers are driving up healthcare costs by failing to "shop around" for cheaper services. As if!

Let me just note that I go to a health practice that is under investigation for being a monopoly -- in PALO ALTO, home of Stanford hospitals and any number of new startups in the healthcare space. Bigger healthcare companies tend to get bigger by merging, and that's a fact. An article on the subject:

And let me again note, this is in an area where we have an abundance of high-quality providers! There are many areas of the US, especially rural ones, where there is basically ZERO choice. My best friend lives in a relatively affluent part of Alaska, but anything beyond the basics means she has to fly to Anchorage where she might have a choice between like 2 specialists in any given field. And that isn't even counting on who takes your insurance, since Alaskans more frequently than most pay cash for everything.

Then let us note that consumers have NO real idea how much they (or their insurance companies) will be paying for anything. Even if you try mightily to get quotes beforehand, the healthcare providers appear to be under no obligation whatsoever to stick to those prices. When I was lying in the surgical ICU at Stanford with a gigantic aneurysm, they sent a guy to make me sign a piece of paper saying they were going to charge me $99K to clip the thing... and in the end it turned out to be twice as hard as they expected, and I ended up owing almost $300K when the bills started trickling in weeks later.

Only once was I ever asked by the insurance company to go to a cheaper provider -- in this case for a CAT scan of my head -- and although I immediately said yes, in the end they decided that the cheaper place was not capable of dealing with the technical issues (because I have metal inside my brain). It's not that I failed to shop around, but even in Palo Alto it turns out there are only 2 places -- both major hospitals -- that had the proper equipment and staff for an even slightly non-routine CAT scan.

And let's not forget that generally you can't switch health insurance plans more than once a year (if that), and that you often can't even see the better doctors because they aren't taking new patients, and you certainly can't see a top specialist without a referral from a primary physician at that same practice... and the whole idea that consumers should be trying to save money by "shopping around" for healthcare is revealed as utterly ridiculous and contrary to reality. That only works in situations, like elective plastic surgery, where insurance is NOT involved and the doctors are motivated to be more transparent about costs.

Those are all excellent points.

I wonder why we consumers get no good idea of how much everything will cost.

Is it because prices vary according to how much they think insurance will pay?

The whole system is a huge mess, and is designed more for the providers and the insurance companies, not to keep the citizens healthy. I feel the deductible system is flawed because it encourages people to delay healthcare that they need, it encourages (if one can help it), to try to stack everything in a single year, and then try to make it many years without using it again, this is a big FAIL!

Trying to get a straightforward factual answer to a price of a medical service is almost impossible, most service providers don't even know, because there are 100's of insurance plans and it depends on what deal they have with each plan, not even each company.

IMO they could hold things to a set price country wide, this would fix a lot of the problems.I can not think of another business that has such a flaky unpredictable billing system. Imagine getting a surprise extra bill from your hotel stay 3 months ago.

The worse thing about this is: you make people tangle with this system when they are sick, sometimes in the worst shape of their lives, fighting for their very lives, it's not right.

One of the other reasons it's hard to get a good idea of what things will cost is that healthcare is the one area where providers -- especially hospitals -- are actually allowed to charge people who can pay (which is generally people with insurance) more money to cover their costs from people who cannot pay!

High deductible insurance causes financial duress:

Deductibles often seem like an unfair trick, or a feature that makes insurance worthless.

I think we can all agree that if fancy cars, tickets to sporting events, and top-shelf boozes were free and unlimited... heck yeah people would consume more of them! But health and education are two commodities that work on different rules than others -- among other things, the vast majority of people do NOT want to consume more -- and it's not entirely clear that limiting consumption even leads to the best outcome except in short-term cash outlay.

I mean, it's not even entirely clear what "cost" means with regard to these two commodities. Look at the experiment referenced above, with the young and well-educated consumers (and by the way, check the economists' assumption here that consumers must be making "irrational" healthcare decisions because they're ignorant). were given cash to cover their deductibles in full. Despite being given enough cash to cover the high deductibles, the test subjects ended up "saving" 12% by postponing health care. You have to assume that some of them will end up having worse health problems in the future due to this decision -- so was it really a cost savings or was it just a cost deferral?

Similarly with education... you've all heard the phrase (attributed to Derek Bok) "If you think education is expensive, try ignorance". But it is all too literally true.

You're right that there are lots of hidden costs in education and healthcare, especially if people don't get them. Basically we pay now or we pay later.

8:25 AM Feb 14 2016