Lack of mobility due to lack of housing liquidity is a core part of the American dream that has changed, and it helps explain why Trump won.

Adam Rifkin stashed this in Personal Finance

Stashed in: Economics!, @troutgirl, Awesome, Jobs, America!, Charts!, Politics 2016, Freakonomics, Trump!, Personal Finance, 2016, Inequality

There are many people under water with their houses in the Midwest, middle Atlantic, and South.

They cannot sell their houses and move to where better jobs are available.

How many people would move to where more jobs are if they could?

One factor that hasn't been discussed a great deal is the housing market. But, according to Markus Schomer, chief economist of PineBridge Investments, the prolonged effects of the financial crisis exacerbated economic issues, which in turns impacted the election result.

"The reason Trump won was because of a part of the country where some of the benefits of the Obama economy haven’t been felt sufficiently," Schomer said in an interview with Markets Insider. "We have seen a lot of the manufacturing jobs leaving and no new jobs being created."

There’s an inequality between the jobs that have been lost in the old manufacturing hubs - places like Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Michigan - and the new jobs created in places like California.

This inequality was then exacerbated by a lingering problem in the housing market.

"Before the great financial market crisis, housing was always a very liquid asset," said Schomer. "If you lose your job in Ohio, you sell your house and move to California, because that’s where all the jobs are. Because of the housing crisis, so many people have been so underwater with their mortgage that they couldn’t do that."

Schomer said:

"For the past six years, that typical mobility that we had in the US, where people would go where the jobs are, has been lost. At the same time, the jobs being created aren’t the kind of jobs that everyone can do. The people who lose their jobs in one industry can no longer just transfer it easily to another industry. There’s a cyclical element here, which is the housing story, and a structural element, that the skill sets are not easily transferable anymore."Geographic mobility within the US has decreased over the past several decades. According to a report by Liberty Street Economics published in October, the percentage of the working-age population (those between 25 and 59) that moved to a different state in a given year stood at 1.5% in 2010, down from 3% in the 1980s.

"The idea of moving across state borders for a job has been woven into the fabric of the American Dream," the report said. "However, the image of the United States as a mobile nation has changed substantially over recent decades."

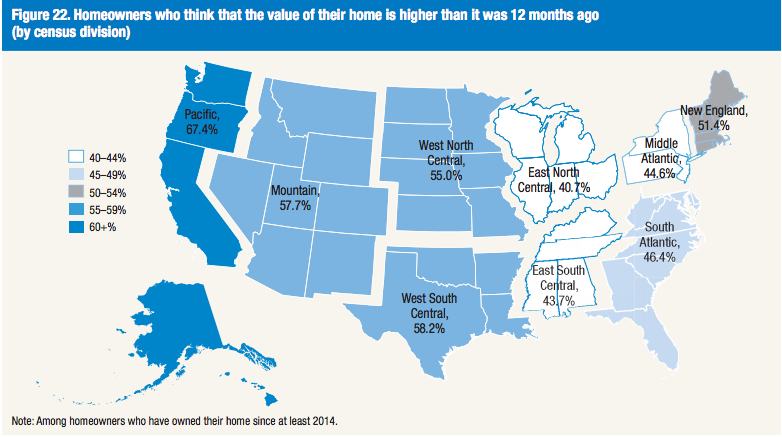

Those in middle America are also much more likely to believe that their homes haven't increased in value.

This chart by the Federal Reserve shows that US homeowners clustered on the coast are the ones that disproportionately feel that the value of their homes have increased. Middle America, where a lot of the jobs have been lost and for whom labor mobility is the most important, are more disullusioned about what their homes are worth.

There was no policy to address these cyclical and structural rifts under the Obama presidency, according to Schomer.

"That’s the one thing that was missing in the last administration," said Schomer, "there was no policy to address the job shortfall in places like Pennsylvania and Ohio. Maybe it should be the state government that does that, but the federal government never developed a strategy."

The fascinating thing to me is that until fairly recently it was considered common sense to buy a house almost anywhere as soon as a family was even remotely able to bear the financial load. It wasn't until Robert Shiller's 2005 second edition of his book _Irrational Exuberance_ that we even faintly started to question whether this orthodoxy was actually a historically contingent blip that profited Baby Boomers but would not be possible for the future generations.

Right.

And even after Case-Schiller won Schiller a Nobel Prize in Economics, many Americans don't realize the downsides of home ownership.

It's still unfortunately conventional wisdom among many that home ownership is all good.

The mortgage deduction itself creates a perception that society values home ownership, even if some particular situations are not ideal for some people who buy homes.

Sorta ironic that white people in the Midwest and South are trapped by the detritus of their former affluence. Meanwhile immigrants and African-Americans, who are far less likely to have developed wealth through home ownership, are at least able to move around more easily to seek jobs.

Those are both good points.

We need to keep encouraging people to learn about the benefit of not owning a home before they make their decision of whether to buy a home.

2:12 PM Dec 26 2016