The automation myth: Robots aren't taking your jobs — and that's the problem...

Joyce Park stashed this in Economics

Stashed in: Economics!, Robots!, Best PandaWhale Posts, Awesome, History of Tech!, Singularity!, Bots, Leisure!, Economics, Robot Jobs, Basic Income, Economics

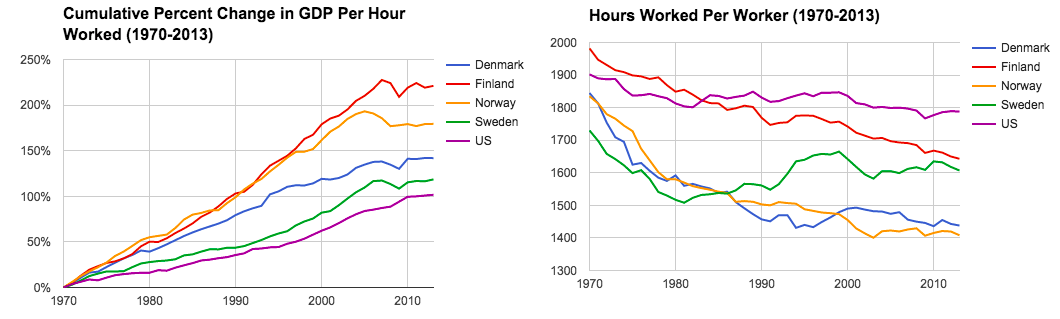

Matt Yglesias argues that we need some productivity growth if we want to enjoy more leisure and healthcare -- and that robots will give us that.

The robots aren't taking our jobs; they're taking our leisure.

Data from the American Time Use Survey, for example, suggests that on average Americans spend about 23 percent of their waking hours watching television, reading, or gaming. With Netflix, HDTV, Kindles, iPads, and all the rest, these are certainly activities that look drastically different in 2015 than they did in 1995 and can easily create the impression that life has been revolutionized by digital technology.

The slowing rate of productivity growth is an important source of the wage slowdown that people have been worrying about:

The 2015 Economic Report of the President calculated that if productivity growth had continued at its 1948–1973 pace for the past 40 years, the average household's income would be $30,000 higher today. By contrast, had inequality stayed at its 1973 level for the same period, Obama's Council of Economic Advisers calculates that the average household's income would be only $9,000 higher.

The productivity issue is bigger than inequality, in other words. And yet it's much less discussed.

In fact, it's almost anti-discussed due to the obsession in media and political circles with the alleged rise of the robots. We're so busy worrying about how to counteract an imaginary, robot-driven productivity surge that we're barely paying attention to the real story of the productivity slowdown.

Most job categories have been affected by digital technology, but only in relatively superficial ways.Â

Something like 9 percent of all private sector jobs are in the food service industry. These days people are perhaps more likely to book a reservation or order a takeout meal with an app rather than a phone call, but the core work of serving and preparing food has seen very little progress.

At the higher end of the salary spectrum, we still don't have robot doctors who can treat patients in lieu of costly and inconvenient human ones. Indeed, we can't even get medical records digitized properly.

As it becomes clearer and clearer over time that smartphones and the internet simply aren't economic game changers on the same scale as air conditioning, jet planes, container ships, and televisions, it's become increasingly fashionable in Silicon Valley to simply retreat into denial.

"There is a lack of appreciation for what’s happening in Silicon Valley," Google's chief economist, Hal Varian, told the Wall Street Journal, "because we don’t have a good way to measure it."

The article states that Varian believes a "problem with the government’s productivity measure" is that "it is based on gross domestic product, the tally of goods and services produced by the U.S. economy."

But this is not a measurement error. This is the definition of economic productivity. When people can create more goods and services for sale in the market economy, their productivity goes up. When they cannot, it does not. It is obviously true that there are things in life that matter that are not monetized in this way. I, personally, derive enormous pleasure from daily jokes on Twitter. That said, Silicon Valley hardly invented the idea that the best things in life are free. The joy that my infant son's smile brings to my face isn't in the GDP numbers either. Nor is the sadness I feel when reflecting on the fact that my late mother didn't live to meet him.

But if you want to put a roof over your baby's head, to keep him in diapers and formula, and to buy some plane tickets so he can go with you to visit his grandparents, then you are going to need some money. And money derives from monetized economic activity.

Thinking about this part of the quote above: "smartphones and the internet simply aren't economic game changers on the same scale as air conditioning, jet planes, container ships, and televisions". I know I'm going to sound like a defensive Silicon Valley type, and maybe I am... but I have doubts about what he's saying.

I'm 100% in agreement about container ships, although bulk shipping is also still massively important because oil. I'll even give you jet planes. But TV and AC, I'm gonna push back on. What was the massive economic impact of TV beyond a subset of advertising? TV is a broadcast medium with just a handful of gatekeepers controlling the whole thing, so little opportunity for the masses to participate rather than consume. And believe it or not, large cities with big office buildings were common before air conditioning... it's really a TYPE of large urban building with glass walls that absolutely needs it. That big spike in productivity from 1948 to 1973? Almost entirely happened before AC was common.

Meanwhile, a lot of the economic impact of the internet is in person-to-person communication, therefore not super obvious in consumer apps that "do things" like pick up your laundry or deliver your sandwiches. Scientific research, for instance, has been and continues to be massively changed by the internet. But also, such a TREMENDOUS amount of cost and benefit in our world today comes from participatory democracy aka political contention. The reason that doctors can't see you online or your medical records can't be properly digitized has nothing to do with technical capabilities and everything to do with lack of consensus about whether those things are good and safe. I've been astonished to learn how few NIMBY types it takes to add millions of dollars and years of delay to projects like my local commuter railroad which is bursting with demand -- while the inability of the traditional powers to meet that demand creates opportunity for quick-moving private companies like Uber. Well, both the political opposition to public transit and the ability to quickly form a company like Uber are made possible by the Internet. If the Internet had existed back in the day, Abe Lincoln and Dwight Eisenhower wouldn't have been able to push through the railroads and highways that built this country!

You make some very good points Joyce.Â

I think you're right that smartphones and Internet are as important for communication and transportation -- the necessities for trade -- as were railroads and highways.Â

9:05 AM Jul 28 2015